- Chapter 18 - Professional Capacity

- 18.1 Introduction

- 18.2 Historical overview

- 18.3 The evolution of legislative and professional approaches to impairment and misconduct

- 18.4 National registration of health practitioners in Australia from 2010

- 18.4.1 Definitions of suitable persons, competence and impairment in the National Law

- 18.4.2 Mandatory reporting of notifiable conduct and notifiable impairment in the National Law

- 18.4.3 Mandatory reporting of a “mentally ill” or a “mentally disordered” practitioner in accordance with Mental Health Acts in the National Law

- 18.5 A holistic view of competence

- 18.6 The science and study of medical health and impairment

- 18.7 The late career medical practitioner: cognitive impairment and other matters

- 18.8 Ageing and retirement

- 18.9 Student impairment

- 18.10 The attitude of doctors to health and impairment: stigma, omnipotence and other matters

Chapter 18 - Professional Capacity

Contributed by Carmelle Peisah with input from Georgie Haysom BSc LLB (Hons) LLM (Bioethics) , current to July 2020.18.1 Introduction

We use the term professional capacity in this text to refer to an individual’s fitness or competence to practise a profession, with specific focus on medicine. No other profession has stimulated the level of legislative or academic interest in its members’ competence to practise professionally. Nevertheless, many of the areas examined in this chapter are of relevance to other health professions, in particular since the introduction of Australia’s Health Practitioner Regulation National Law. We describe the evolution of medical licensing and regulation, including legislative and professional approaches to the concept of professional capacity and conversely, impairment and misconduct, as they relate to both students and doctors.18.2 Historical overview

18.2.1 The origins of medical licensing and professional regulation in the United Kingdom

The licensing of medical practitioners has its roots in the United Kingdom (UK). However, the recognition and consolidation of the medical profession as such lagged behind its more revered professional predecessors, the religious and legal professions (1) The first emergence of regulation was initiated from within the profession with the petitioning in 1421, of a group of physicians to the Houses of Parliament, seeking to regulate medical practice due to concerns about the consequences of unregulated practise:many uncunning and unapproved in the aforesaid Science practises, and especially in Physic, so that in this realm is every man, be he never so lewd, taking upon him practise, be suffered to use it, to…. great harm and slaughter of many men: (2)In that same petition there was a call for legislation that enforced regulation of standards of training for the profession, with consequences for non-compliance (3):

no man, of no manner, estate, degree, or condition, practise in Physic, from this time forward, but he have long time used the Schools of Physic within some University, and be graduated in the same; that is to say, but he be Bachelor or Doctor of Physic having Letters testimonials sufficience of one of those degrees of the University in the which he took his degree in; under pain of long imprisonment, and paying f40 to the King; and that no Woman use the practise of Physic under the same pain.Although parliament responded to the petition by acknowledging the “evils inflicted on the people by ignorant practitioners in physic and surgery”, (4) and granting the King's Council the power to punish the unskilled and unlearned, there is little evidence that the Council was particularly active in this function. In 1511, regulation of the profession was put into the hands of the Church, considered to be the only institution with the authority, power, and organisational structure to serve as a disciplinary body (5). A statute was passed that allowed a practitioner to obtain a medical licence from the Church, after examination by four Doctors of Physic. (6) In 1518, the College of Physicians was established, albeit primarily focused on the London profession, with the Universities (Oxford and Cambridge) and the Church otherwise maintaining their primary licensing roles. Medicine continued to be regulated by the universities and the ecclesiastic authorities until 1858 when the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Medical Act 1858, to regulate the Qualifications of Practitioners in Medicine and Surgery. (7) The Act stated:

It is expedient that Persons requiring Medical Aid should be enabled to distinguish qualified from unqualified Practitioners. (8)This Act created the position of Registrar of the General Council of Medical Education, and provided for registration of medical practitioners in the UK. The 1950 Medical Act introduced disciplinary boards and a right of appeal to the General Medical Council and formally renamed the Council as the General Medical Council (GMC) (9)

18.2.2 The evolution of medical licensing and professional regulation in Australia

Preceding the establishment of the GMC in the UK, the first regulation of the medical profession in Australia occurred in 1837 with the creation of the Medical Council of Van Diemen’s Land. In 1838, New South Wales passed No. XX11 An Act to define the qualifications of Medical Witnesses at Coroner's Inquests and Inquiries held before Justices of the Peace in the Colony of New South Wales. (10) The Act put in place the concept of registration (a publicly available list of legally qualified doctors), requirements for registration and a Board to oversee such. This established the NSW Medical Board comprising at least three members and a register of qualified practitioners with the following requirements for qualifications:a Doctor or Bachelor of Medicine of some University or a Physician or Surgeon licensed or admitted as such by some College of Physicians or Surgeons in Great Britain or Ireland or a Member of the Company of Apothecaries of London or who is or has been a Medical Officer duly appointed and confirmed of Her Majesty's sea or land service.Initially registration was voluntary, but the legislation was steadily tightened, until unregistered medical practice was effectively illegal. (11) The Legally Qualified Medical Practitioners’ Act 1855 (NSW) consolidated the status and authority of the NSW Medical Board. The Medical Practitioners’ Act 1898 (NSW) repealed the earlier legislation and further established the specific requirements for persons to be deemed “legally qualified medical practitioners” suitable for registration, namely any person:

- who proves to the satisfaction of the NSW Medical Board that he is:

- a doctor or bachelor of medicine of some university, or a physician or surgeon licensed or admitted as such by some college of physicians or surgeons in Great Britain or Ireland; or

- that he has passed through a regular course of medical study of not less than three years' duration in a school of medicine, and that he has received, after due examination, from the University of Sydney or from some university, college, or other body duly recognised for that purpose in the country to which such university, college, or other body belongs, a diploma, degree, or license entitling him to practice medicine in that country ;

- or that he is a member of the Company of Apothecaries of London, or a member or licentiate of the Apothecaries' Hall of Dublin.

- Any person who is or has been a medical officer duly appointed and confirmed of Her Majesty's sea or land service(12)

18.3 The evolution of legislative and professional approaches to impairment and misconduct

It can be seen that licensing and regulation of the profession emerged out of concerns for the safety of the public, acknowledged as far back as 15th century England. It took four centuries to address this with registration predicated upon increasingly rigorous qualifications and training, public records of registered doctors, and Medical Boards or Medical Councils to regulate and act as gatekeeper of such. While entry to the profession had been increasingly refined, processes for exit from the profession had not been regulated until the turn of the 20th century. In 1900, NSW Parliament passed legislation that empowered the Medical Board to remove the name of a medical practitioner from the register of practitioners, if the Board after an inquiry was satisfied that that practitioner had been convicted of a felony or misdemeanour (13) In 1938, in addition to having been convicted of a felony or misdemeanour, further exclusion criteria for registration were added with the Medical Practitioners Act 1938 (NSW). Notably, the Medical Board was empowered to refuse registration to anyone:(6)This legislation was the forerunner of our current approach to impairment and professional capacity in doctors, namely that professional capacity may be affected by criminal conduct, misbehaviour or poor conduct, and health – the latter attributable to physical illness or mental disorder including substance disorder. More importantly, the Act made it clear that such exclusion could not be on the basis of trivial matters but rather those that put the public at risk, the misunderstanding of this high threshold persisting almost a century later with doctors avoiding treatment for fear of notification. Similarly, in 1958, the United States Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) identified drug addiction and alcoholism in doctors as a disciplinary problem. (15) This body also recommended the development of a model program of probation and rehabilitation for practitioners so afflicted. The notions of professional capacity or competence, and conversely, impairment continued to evolve. For example, in 1972, the American Medical Association defined practitioner impairment as:The board shall not refuse to register the name of any person on the ground specified in paragraph (a) of this subsection when the offence was not from its trivial nature or from the circumstances under which it was committed such as to render such person unfit in the public interest to practise his profession …. and (7). No person shall be registered under this Act unless the board is satisfied that such person is of good character.(14)

- who has in New South Wales been convicted of a felony or misdemeanour or elsewhere of any offence which if committed in New South Wales would have been a felony or misdemeanour; or

- whose name has been, for any reason affecting the conduct of such person in any professional respect, erased or removed from any register or roll established or kept under any law in any other part of the British Empire or in any foreign country providing for the registration or certification of medical practitioners under a public authority; or

- who is of unsound mind or has been guilty of habitual drunkenness or of addiction to any deleterious drug.

the inability to practice medicine with reasonable skill & safety … by reason of physical or mental illness, including deterioration through the aging process, the loss of motor skills, or the excessive use or abuse of drugs, including alcohol. (16)The Medical Practice Act 1992 (NSW), stipulated that a person was entitled to registration as a medical practitioner if they had recognised medical qualifications and had successfully completed a period of internship or supervised training. (17) More tellingly, the Act stated that registration could be refused despite entitlement or eligibility on the grounds of qualifications and training. The Board could not register a person as a medical practitioner unless satisfied that the person:

Also the Act defined impairment as follows:

- was competent to practise medicine (that is, the person has sufficient physical capacity, mental capacity and skill to practise medicine and has sufficient communication skills for the practice of medicine, including an adequate command of the English language); and

- was of good character. (18)

A person is considered to suffer from an impairment if the person suffers from any physical or mental impairment, disability, condition or disorder which detrimentally affects or is likely to detrimentally affect the person’s physical or mental capacity to practise medicine. Habitual drunkenness or addiction to a deleterious drug is considered to be a physical or mental disorder. (19)Further, the Medical Practice Act 1992 (NSW) made provision for conditions of practice that could be imposed in cases of impairment:

The Board may impose conditions on a person’s registration if the Board is satisfied that the person suffers from an impairment, and the conditions are reasonably required having regard to the impairment. (20)The Medical Practice Act 1992 (NSW) also restated the provision in the 1900 Act that empowered the Medical Board to remove the name of a medical practitioner from the register of practitioners if it was satisfied that that practitioner had been convicted of a felony or misdemeanour. The 1992 Act specifically provided that the Medical Board could refuse an applicant registration if they had been convicted in NSW of an offence, or had been convicted elsewhere by a court for, or in respect of, an act or omission that would have constituted an offence, had it taken place in New South Wales. However, before it could do so, the Board had to form the opinion that the conviction rendered the applicant unfit in the public interest to practise medicine. In making its decision, the Board had to have regard to the nature of an offence, such as whether it was of a trivial nature, and the circumstances in which it was committed. (21) As such, being of good character, or not as is the case here, and being convicted of significant felonies have since served as one of the grounds for de-registration. In 2000, the NSW Medical Tribunal found that a practitioner, a psychiatrist, was not of good character. This was on the basis of harassment and intimidation of a witness to the offences of which he was convicted as well as for the convictions themselves. The practitioner was also found unfit in the public interest to practise medicine because of the nature of the criminal offences, namely malicious wounding and intimidation with intent to cause fear. In its reasons for decision, the Tribunal stated:

The Tribunal considers that for a person to be of good character for the purposes of the practice of medicine as a registered medical practitioner, it is imperative that his or her character be such that he or she will not deliberately do any harm to another person, at least without reasonable excuse, and that he or she will not commit major serious offences against the criminal law. After all, the practice of medicine is designed to prevent or alleviate suffering, not to inflict it.(22)

18.3.1 Reportable impairment and reportable misconduct

Notwithstanding these advances in regulation, the notion of reportable misconduct or reportable impairment was late to emerge, and only did so this century in response to two cases which highlighted gaps in the regulatory systems’ processes for protecting the public. The first case involved a general practitioner who ran an abortion clinic and had been the subject of multiple complaints pertaining to terminations of pregnancy in five women, culminating in a manslaughter charge. In October 2005, the Medical Tribunal found the practitioner guilty of unsatisfactory professional conduct and professional misconduct, as well as being not of good character, ordering that the practitioner be deregistered and not apply for re-registration for ten years. (23). What caught the attention of the public was subsequent media reporting in August 2006 after this practitioner was convicted by a jury of giving drugs to a woman illegally to procure a miscarriage. Newspaper reports emphasised that the jury had been unaware of previous complaints about the practitioner that included multiple contacts with the Medical Board; six cases brought against her for damages, some relating to failed abortions in the District Court and all settled out of court; as well as a trial for defrauding Medicare. (24) In August 2006, the Minister for Health announced an urgent review of the powers of the NSW Medical Board under the Medical Practice Act 1992, to improve the way in which the system operated to protect the public. Further review of the subsequent Medical Practice Amendment Bill 2008 that emerged from this was prompted by public concern over the manner in which the regulatory system had dealt with (or failed to deal with) a second case over a prolonged period from the 1990s to his final de-registration in 2004 (25) The second case, reported in even more salacious detail by the media (26) involved the public hospital appointment of a specialist in obstetrics and gynaecology, despite the order of a Medical Board Professional Standards Committee five years earlier that banned the practitioner from the practise of obstetrics (27) In the course of 15 years at another hospital the practitioner had been the subject of 35 complaints related to alleged bullying of staff and patients, humiliating junior medical and nursing staff in front of patients, failing to communicate with colleagues about clinical matters, and failing to offer adequate anaesthetic and analgesia to patients during procedures. (28) A Board appointed psychiatrist could find no evidence of a psychiatric disorder but stated the practitioner experienced “troublesome personality traits”. (29) Shortly after the practitioner’s appointment, the practitioner’s employer contacted the Board to discuss concerns about the practitioner’s performance. It was at this time that the employer discovered that the practitioner had been excluded from practising obstetrics. The Medical Tribunal eventually found that the practitioner had engaged in professional misconduct of the most serious kind by deliberately failing to inform employers of the limiting clinical practice order. (30) Following these two very public failures of the system, the Medical Practice Amendment Act 2008 (NSW) made amendments to both the Medical Practice Act 1992 and the Health Care Complaints Act 1993. In addition to empowering the Medical Board to (i) take urgent action to protect the public under Section 66 of the Medical Practice Act 1992; and (ii) to have regard to any previous complaints and adverse findings against the practitioner; and changing the composition of the Professional Standards Committee, the Medical Practice Amendment Act 2008 (NSW) imposed mandatory reporting obligations on medical practitioners to report “reportable misconduct” by their colleagues under the following circumstances:if he or she practises medicine while intoxicated by drugs (whether lawfully or unlawfully administered) or alcohol, if he or she practises medicine in a manner that constitutes a flagrant departure from accepted standards of professional practice or competence and risks harm to some other person, if he or she engages in sexual misconduct in connection with the practice of medicine.As we discuss below, reportable conduct and reportable impairment were further refined with the various Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Acts.

- A medical practitioner who fails to report ‘reportable misconduct’ commits unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct. (31)

18.4 National registration of health practitioners in Australia from 2010

The National Registration and Accreditation Scheme for health professionals commenced on 1 July 2010, (except in Western Australia, where the scheme commenced 18 October 2010) recommended by the 2006 Productivity Commission and accepted by the Council of Australian Governments in 2008, to reduce administrative demands on, and enhance the mobility of professionals (32) This provided for national registration and regulation of ten health professions, including medical, nursing and midwifery, dentists and psychologists. Other professions have subsequently joined the national scheme so that 14 professions are now represented in the scheme. As the Commonwealth lacked the constitutional power to enact stand-alone Federal legislation, the first step in establishing the national statutory scheme was achieved when the Queensland Parliament enacted the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009. (33)(see Haysom G. (2015) Review of the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme. Australian Health Law Bulletin, vol 23: 12-15). This legislation was adopted under the principles of mutual recognition by other states and territories, with amendments appropriate to each jurisdiction while maintaining participation in the national scheme. (34) Western Australia was the last jurisdiction in which the National Law commenced on 18 October 2010. As medical practitioners are subject to the National Law as it is in force in each state and territory, care must be taken to ensure that reference is made to the particular national law as enacted in each jurisdiction as there are some significant differences, primarily in NSW and Qld which are “co-regulatory jurisdictions.” For instance, in NSW, sections of the original enactment by the Queensland parliament were not brought into the National Law (NSW).NSW did not adopt Part 8 relating to complaints handling from the start of the scheme and subsequently Queensland passed the Health Ombudsman Act 2013 to set up a co-registration scheme for complaint handling. The other main difference is in the treating practitioner exemption from mandatory reporting in Western Australia. Otherwise the legislation is essentially the same in all other states/territories. (Haysom G. (2015) Review of the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme. Australian Health Law Bulletin, vol 23: 12-15).18.4.1 Definitions of suitable persons, competence and impairment in the National Law

The National Law has continued to define eligibility for general registration according to appropriate qualifications, and the practitioner being a suitable person, a broad term that encompasses impairment, misconduct and criminal behaviour. Reasons stipulated by the Heath Practitioner Regulation National Law that a health professional is “not a suitable person” for registration are:Under the Heath Practitioner Regulation National Law, a finding of impairment may warrant a further finding of incompetence. Section 149C(1) of the National Law provides that the Tribunal may order that a person be deregistered ‘if the Tribunal is satisfied (a) that the person is not competent to practise medicine’. Section 139 provides that a person is competent to practise their profession if the person has:

- an impairment that would detrimentally affect the person’s capacity to practise the profession to such an extent that it would or may place the safety of the public at risk; or

- a criminal history such that the professional is not an appropriate person to practise or it is not in the public interest; or

- insufficient communication skills in English; or

- previous practice of the profession was not sufficient, or

- failure to meet an approved registration standard, or

- In the Board’s opinion, the individual is for any other reason-

- not a fit and proper person for general registration in the profession; or

- unable to practise the profession competently and safely. (35)

Further, s.178 of the Heath Practitioner Regulation National Law allows the Board to take action if among other things the practitioner has or may have an impairment; and s.196 gives a Tribunal power to decide if a practitioner has an impairment and impose conditions, issue a caution or reprimand, suspend or cancel registration. An Impairment is defined as:

- sufficient physical capacity, mental capacity, knowledge and skill; and

- sufficient communication skills, including an adequate command of the English language. (36)

a physical or mental impairment, disability, condition or disorder (including substance abuse or dependence) that detrimentally affects or is likely to detrimentally affect— (a) for a registered health practitioner or an applicant for registration in a health profession, the person’s capacity to practise the profession;(37)In defining “Impairment”, the National Law requires the presence of a mental or physical condition that, either detrimentally affects or, is likely to detrimentally affect the person’s capacity to practise medicine. The distinction between disorder and Impairment is crucial; the presence of a disorder per se does not constitute Impairment. As we discuss below, doctors, like the rest of the community, suffer from a range of physical and mental illnesses which, when treated and not affecting practice, do not constitute Impairment or grounds for notification. Conversely, a practitioner may experience Impairment in the absence of a formal diagnosis of a particular mental disorder. As the NSW Court of Appeal pointed out in a 2003 case; once the Tribunal came to the conclusion that whatever it was that the former doctor suffered from was prejudicial to an orderly conduct of their mental and physical duties as a medical practitioner, the Tribunal was entitled to make a finding of Impairment even although it did not put a psychological label on that Impairment. (38) It is important to note further, that meeting the National Law’s definition of an Impairment does not necessarily equate with the inability to practise or the loss of registration. Consistent with principles of rehabilitation embedded within most regulatory systems, most practitioners with a stable or treated mental disorder who come to the attention of the National Board will ultimately continue to practise with appropriate practice and health conditions imposed. It would be expected that at times of illness the practitioner would seek and accept appropriate medical and other health care, limit or cease their practice, and notify the relevant authority. Beyond Impairment, being a fit and proper person remain important exclusion criteria for being a Suitable Person, and for maintaining public confidence in the medical profession. In 2013, a neurosurgeon was found not to be a suitable person to hold registration, in relation to the supply of a prohibited drug, breach of bail conditions, and making false and misleading statements to the Medical Board in relation to compliance with conditions of practice. (39) (The practitioner was also convicted on a charge of manslaughter and two charges of the supply of a prohibited drug).He pleaded guilty and was convicted of three offences: one of manslaughter and two of supply of prohibited drug (cocaine) (40) In its decision the NSW Medical Tribunal stressed that its role was not to punish, but to make orders that were protective of both the public and the profession. It quoted, as an appropriate starting point, a 1943 UK judgment:

The high reputation of the medical profession as a whole depends in no small measure on excluding from it those whose professional misconduct makes them unworthy to belong to it, and the confidence which the public are accustomed to put in the family doctor is intimately connected with the assurance that those who practise the art of medicine are, in all relations with their patients, individuals of the highest honour. (41)In that same 2013 case the practitioner stated:

I have brought the profession into disrepute, and I have breached my professional obligations to my colleagues, and in some circumstances my patients. (42)

18.4.2 Mandatory reporting of notifiable conduct and notifiable impairment in the National Law

With regards to notifiable conduct and impairment, the National Law stated that employers, education providers and health practitioners have a legal obligation for “mandatory reporting” of “notifiable conduct” about any other registered health practitioner or student, to the relevant board through the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra), which refers the notification to the appropriate body. This equally applies between practitioners, such that nurses and psychologists have a duty to report notifiable conduct in a medical practitioner and vice versa. An example of a National Law definition of “Notifiable conduct” is seen in the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law:notifiable conduct, in relation to a registered health practitioner, means—Similarly, Mandatory notifications by health practitioners is defined as such:

- practising the practitioner’s profession while intoxicated by alcohol or drugs; or

- engaging in sexual misconduct in connection with the practice of the practitioner’s profession; or

- placing the public at risk of substantial harm in the practitioner’s practice of the profession because the practitioner has an impairment; or

- placing the public at risk of harm because the practitioner has practised the profession in a way that constitutes a significant departure from accepted professional standards. (43)

The provisions in the National Law contains a number of exemptions to the mandatory notification obligation including a reasonable belief that someone else has already made a notification. (44) Notably, employers have similar mandatory reporting obligations. If they believe that a registered health practitioner has behaved in a way that constitutes notifiable conduct, the employer must notify the National Agency of the notifiable conduct. They are similarly protected from civil, criminal and administrative liability for persons who, in good faith, make a notification under this Law. Section 237(3) provides that the making of a notification does not constitute a breach of professional etiquette or ethics or a departure from accepted standards of professional conduct and nor is any liability for defamation incurred. However, if the National Agency becomes aware that the employer has failed to notify the Agency of notifiable conduct then the Agency must give a written report about the failure to the responsible Minister for the participating jurisdiction in which the notifiable conduct occurred, who in turn must report the employer’s failure to a health complaints entity, the employer’s licensing authority or another appropriate entity in that participating jurisdiction. (45) There are a number of important principles embodied in these mandatory reporting laws. Firstly, notifiable conduct is clearly defined and involves risk of substantial harm to the public or a significant departure from accepted professional standards, which albeit very subjective, are high thresholds. Secondly, there is protection from civil, criminal and administrative liability for anyone who makes a notification in good faith. Thirdly, on the other hand failure to make a notification, while does not constitute an offence, may constitute behaviour for which action may be taken. Fourthly, employers are equally obliged to make notifications with consequences for not doing so, and if a practitioner considering making a notification about a fellow practitioner is reasonably aware that someone else is making a notification they are exempt from doing so. Finally, mandatory notifications equally apply to students, as discussed later in Section XXX. Studies of mandatory reporting in Australia have shown that the yield from mandatory reporting has been quite heterogenous, and there is wide variation in reporting rates by jurisdiction, sex and profession. A study of 819 mandatory notifications made in each jurisdiction (apart from NSW) during the period 1 November 2011 to 31 December 2012 showed that 62% were for a departure from accepted standards, 17% for practising with an impairment, 13% for practising whilst intoxicated and 8% for sexual misconduct associated with clinical practice. (46) In this study, almost 90% of notifications involved a doctor or nurse as either a notifier or respondent. Male health professionals were more than twice as likely to be the subject of a notification than female practitioners. The authors noted that this was consistent with other research, which has shown that male doctors were more likely to be the subject of patient complaints, disciplinary action and litigation. Possible factors for this male preponderance were greater patient consultations, a tendency to be overrepresented in certain medical specialties such as surgery, and sex differences in communication style and risk-taking behaviour (47). The low rate of notifications made by nurses against doctors (3%) despite being best placed to observe the practice of doctors, and the five-fold variation across different jurisdiction, have led to concerns about underreporting. Postulated reasons for this included a lack of awareness of this requirement of the National Law, a potential notifier’s fear of retaliation and loyalty to a professional or institutional colleague (48). One particularly controversial aspect of mandatory notification is that the onus to report is on the treating health professional who believes that, in the course of providing care to another health professional, that the person receiving care has engaged in notifiable conduct. This has led to arguments that this involves a breach of patient confidentiality and reduces chances of medical practitioners, for instance, seeking help. Strong advocacy on behalf of this view led to this particular aspect of mandatory notification being exempt in Western Australia. In practice, it is usual for treating practitioners to encourage their patient to first make a self-notification, which is then followed by a mandatory notification by the treating practitioner. (49) Review of all mandatory notifications made against health practitioners showed that only 8% were made by treating practitioners. It is far more likely that a report is made by someone other than a regular treating practitioner, and during a period of acute mental illness or intoxication in the health practitioner. (50) Regardless of whether mandatory notification is in place or not, it is usual for treating practitioners to encourage their patient to first make a self-notification, which is then followed, if mandated within the the jurisdiction, by a mandatory notification by the treating practitioner. In order to address these issues, in 2019 amendments to the National Law with regards to notification established a new, higher risk threshold for treating practitioners, which further limited the circumstances for treating practitioners to make mandatory notifications. These changes were made to ensure health practitioners have confidence to seek treatment for health conditions, while still protecting the public from harm. For example, amendments to the mandatory reporting requirements were passed by the Queensland Parliament earlier in 2019 (51). The amendments further limit the circumstances that would trigger treating practitioners compared to other notifier types (non-treating practitioners, employers and education providers) to make a mandatory notification (except with regard to sexual misconduct). Importantly, to give practitioners confidence to seek help if they need it, the threshold for reporting and the circumstances for making a mandatory notification about impairment, intoxication and a departure from professional standards are more limited for treating practitioners than other groups of notifiers. Specifically, the threshold is based on a different level of risk, namely placing the public at substantial risk of harm not merely risk of harm. Treating practitioners in Western Australia providing a health service to a practitioner-patient or student are exempt from the requirement to make a mandatory notification. However, these practitioners still have a professional and ethical obligation to protect and promote public health and safety, so they may consider whether to make a voluntary notification. In 2020, in preparation for these changes to Mandatory Notification requirements in effect from March 2020, the Ahpra published a range of Guidelines regarding legislative requirements for Mandatory Notification(52) The new section related to this in the legislation, s.141B states:Note. See section 237 which provides protection from civil, criminal and administrative liability for persons who, in good faith, make a notification under this Law. Section 237(3) provides that the making of a notification does not constitute a breach of professional etiquette or ethics or a departure from accepted standards of professional conduct and nor is any liability for defamation incurred

- This section applies to a registered health practitioner (the first health practitioner) who, in the course of practising the first health practitioner’s profession, forms a reasonable belief that—

- another registered health practitioner (the second health practitioner ) has behaved in a way that constitutes notifiable conduct; or

- a student has an impairment that, in the course of the student undertaking clinical training, may place the public at substantial risk of harm.

- The first health practitioner must, as soon as practicable after forming the reasonable belief, notify the National Agency of the second health practitioner’s notifiable conduct or the student’s impairment.

- A contravention of subsection (2) by a registered health practitioner does not constitute an offence but may constitute behaviour for which action may be taken under this Part.

(5) In considering whether the public is being, or may be, placed at substantial risk of harm, the treating practitioner may consider the following matters relating to an impairment of the second health practitioner or student—Importantly, mandatory notification requires Impairment (as defined under the National Law, which implicitly requires impact on practice) plus Substantial Risk to the Public. Factors including circumstance, practice context, controls such as oversight and incident reporting, and other arrangements can affect the level of risk –– and the need to report. Ahpra defines reasonable belief:

- the nature, extent and severity of the impairment;

- the extent to which the second health practitioner or student is taking, or is willing to take, steps to manage the impairment;

- the extent to which the impairment can be managed with appropriate treatment;

- any other matter the treating practitioner considers is relevant to the risk of harm the impairment poses to the public.

Direct knowledge (not just a suspicion) of the incident or behaviour that led to a concern. As a practitioner or employer, you are most likely to do this when you directly observe the incident or behaviour. Speculation, rumours, gossip or innuendo are not enough to form a reasonable belief. You may have a report from a reliable source or sources about conduct they directly experienced or observed. In that case, you should encourage the person with the most direct knowledge of the incident or behaviour to consider whether to make a notification themselves. Your professional background, level of insight, experience and expertise will help you form a reasonable belief. Mandatory notifications should be based on personal knowledge of reasonably trustworthy facts or circumstances that would justify a person of reasonable caution, acting in good faith, to believe that the concern and a risk to the public exists. These principles about forming a ‘reasonable belief’ come from legal cases. In short, a reasonable belief is a state of mind based on reasonable grounds. It is formed when all known considerations, including matters of opinion, are objectively assessed and taken into account. (53).Ahpra also defines acceptable professional standards:

includes reference to documents like the code of conduct and guidelines. It covers both practice and professional behaviour. You must understand the standards for that profession to judge whether there has been a significant departure from them. If a practitioner’s practice shows a significant departure from accepted professional standards that places the public at risk of harm, it can trigger a mandatory notification. A significant departure is serious (not slight or moderate) and would be obvious to any reasonable practitioner.Additional factors to be taken into account with regards to professional standards include the circumstances (how isolated the incident is), practice context (e.g. part of an integrated team or not), extent of self-reflection (action underway to redress gaps in practice; how reflective and insightful the practitioner is),controls such as oversight and attitude towards compliance with professional standards, incident reporting and extent of harm can affect the level of risk, and the need to report (54). Notably, Ahpra (telephone number on 1300 419 495) deals with concerns and notifications about student or a registered health practitioner’s health, conduct or performance for all States and Territories other than NSW or Queensland (QLD) (except for statutory offences where AHPRA remains the national contact). For concerns regarding a registered health practitioner’s health, conduct or performance in NSW, contacts include

- the NSW Health Professional Councils Authority via its website or by phoning 1300 197 177 (if your query is about a medical practitioner or student in NSW, phone (02) 9879 2200); or

- NSW Health Care Complaints Commission via its website or by phoning 1800 043 159 or (02) 9219 7444.

18.4.3 Mandatory reporting of a “mentally ill” or a “mentally disordered” practitioner in accordance with Mental Health Acts in the National Law

For example, in NSW if a registered health practitioner or student is found to be a mentally ill person or a mentally disordered person in accordance with section 27 of the Mental Health Act 2007 , the person prescribed by the NSW regulations must notify:- the Executive Officer of the Council for the health profession in which the registered health practitioner or student is registered; and

- the National Board for the health profession in which the registered health practitioner or student is registered. (Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (NSW) No 86a Part 8 Division 3 Subdivision 8 s 151)

18.5 A holistic view of competence

As we have stated above, the National Law defines competence broadly: sufficient physical capacity, mental capacity, knowledge, skill and communication skills to practice. What are the physical and mental capacities, knowledge and skills sufficient to practise the profession of medicine? Epstein has defined competence as comprising habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and reflection in daily practice, for the benefit of the individual and community being served. (55). The use of the word “habitual” is important here. Professional competence must be maintained but there is also recognition that it is a dynamic construct that is developmental, impermanent and context dependent. One way to ensure that competence is habitual is continuing medical education (CME) or continuing professional development (CPD), a prerequisite for renewing registration in many jurisdictions. Such programs may serve the basis for revalidation processes in the future, which are themselves an altogether more controversial means of ensuring ongoing competence (56) Another contemporary view of competence is the notion of the culturally versed physician - a goal of the vast majority of medical schools and specialty training programs in the western world (57) This has been driven by the concept of globalisation, from which medicine is not exempt, and recent changes in western nations, which have become multi-ethnic and socially diverse societies. Cultural competency is demonstrated by an awareness that each clinical presentation is potentially associated with a myriad of culturally shaped ways in which health, illness, healing and death are perceived. Other contemporary perspectives reflect changes from paternalistic and unitary models of care. This means that modern competency is predicated upon a commitment to collaborative decision-making with the patient and their family, and an understanding that the patient is best managed by a multidisciplinary team of health professionals with diverse, but complementary, skills. Many of these principles are embodied within the Medical Board of Australia’s Code of Conduct, articulated in Good Medical Practice (the Code), which outlines what is expected of all doctors registered to practise medicine in Australia. Although the Code specifically states that it is not a substitute for the provisions of legislation and case law, it does set and maintain standards of practice against which a doctor’s professional conduct can be evaluated. Duties of practising doctors include: (i) to make the care of patients the doctor’s first concern; (ii) to practise medicine safely and effectively; (iii) to be ethical and trustworthy and display qualities such as integrity, truthfulness, dependability and compassion; (iii) to not take advantage of patents; (iv) to protect patient confidentiality; (iv) to protect and promote the health of individuals and the community; (v) to demonstrate cultural awareness; (vi) to display good communication; (vi) to demonstrate self-awareness and self-reflection, including reflecting regularly on whether they are practising effectively, on what is happening in their relationships with patients and colleagues, and on their own health and wellbeing; (vii) a duty to keep their skills and knowledge up to date, refine and develop their clinical judgement as they gain experience, and contribute to their profession. (58) Although based on similar components as our legislative definitions of competence of professional performance, conduct, convictions, physical and mental health, United Kingdom’s Medical Act (1983) uses the term “fitness to practise,” instead of competence, (59). Accordingly, the General Medical Council has produced two documents, one directed primarily at medical schools and universities on Fitness to Practise (60)and another elaborating on Good Medical Practise (61), similar to that articulated by the Medical Board of Australia (62) These documents provide a framework for addressing health and behaviour, and articulate the standards of professional behaviour expected of doctors and students alike, with reference to knowledge skills and performance, safety and quality, communication, partnership and teamwork and maintaining trust. Teamwork and working with colleagues in the ways that best serve patients' interests is an important yet often neglected aspect of professionalism defined by the GMC. (63). Non-collegial behaviour has increasingly come to light in recent times in the face of very public withdrawals of College accreditation of hospital-based medical units due to bullying and other manifestations of dysfunctional physician behaviour. This shows that failure to work with colleagues in ways that do not serve patient interests can not only present as an individual practitioner problem – as discussed below in Section 18.5.2 in reference to Personality Disorders - but a cultural problem endemic in medicine.18.6 The science and study of medical health and impairment

As we have repeatedly stated, there is a very clear distinction between statutory defined Impairment, a threshold concept related to competency to practise, and the experience of physical and mental disorders. It can be seen from the very first acknowledgment of health having an impact on medical practice in the Medical Practitioners Act 1938 (NSW), by virtue of (amongst other disorders) “an unsound mind”, that this threshold has always been high. However, this has always been misunderstood by the profession, who have retreated from the proper recognition and treatment of illness due to shame and fear of consequences on practice (64), compounded by defensive omnipotence and denial of vulnerability (Henderson M. et al, (2012) Shame! Self-stigmatisation as an obstacle to sick Doctors returning to work: a qualitative study BMJ Open 2:e001776), with consequences of neglecting health and failing to protect the public and regulate the profession. It is therefore important to understand medical impairment across its full spectrum, to understand the distinction between the experience of mental and physical disorders per se by doctors, and those that cause Impairment. Doctors, as do the rest of the community, suffer from a range of disorders, some specialities more than others, in part due to the nature of the work and in part due the opportunistic availability of substances for example. Capturing accurate prevalence data about doctor illness has always been problematic due to the aforementioned denial and evasion of detection and treatment, and most work has been based on regulatory data, albeit clearly biased towards severity. For example, a study of 181 doctors who referred to the then NSW Medical Board Health Programme between 1993 and 2001, showed that the largest cause of impairment was psychiatric illness, with male doctors over-represented, with an average age of 41.6 years, and most likely to be working in emergency medicine or psychiatry (Pethebridge A. (2005) Rehabilitation of the Impaired doctor. Master of Medicine by Thesis. UNSW).18.6.1 Anxiety, depressive and substance use disorders, suicide

The common mental disorders experienced in the community - depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and substance use disorders - are those that are predominantly experienced by medical practitioners. As stated above, the exact prevalence of these disorders in medical practitioners is unclear. This is due to methodological difficulties in studies based purely on regulatory data which capture only the cohort of doctors who have come to the attention of regulators due to severity of disease. Even surveys of the profession as a whole are strongly contaminated by response bias and the reliability of self-report data. Nevertheless, data from the largest Australian survey of its type, the National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students, are extremely telling (65) For example, the Survey showed that doctors reported substantially higher rates of psychological distress when compared with the general population and other professionals (66) Approximately 21% of doctors reported a lifetime diagnosis of, or treatment for, depression, whilst 6.2% reported a current diagnosis. The current level of depression in doctors was similar to that in the general population, but higher than in other professionals (5.3%). Approximately 9% of doctors reported having ever been diagnosed with, or treated for, an anxiety disorder (population rate 5.9%). Some 3.7% reported a current diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (population rate 2.7%). Between 14.6% (in the 61years + group) and 27.6% (in the 18-30 group) of doctors reported having thoughts of taking their own life prior to the last 12 months, and 10.4% reported having these thoughts within the last 12 months. Rates of suicidal ideation were highest for those working in mental health, in non-clinical roles, emergency medicine and anaesthetics. Approximately 2% of doctors reported having ever attempted suicide. (67). Rates of suicidal ideation were slightly higher for female then male doctors but females have double the rate of attempted suicide (1.6% compared with 3.3%). A study of Australian coronial data of all health professionals reported similar gender difference in completed suicide. Female doctors were 2.5 times more likely to die by suicide than women in other occupations, whereas the rate in male doctors was no higher than in other occupations (68) The highest rate of suicide was in female nurses. In particular, the rate of suicide was 1.6 times higher in health professionals with ready access to prescription drugs than professionals without such access. The significance of substance use has long been recognised, both in the early regulatory legislation and in the literature. We have known for over 30 years that psychoactive drug use amongst doctors – particularly younger doctors - is higher than in the general population (Domenighetti G., Tomamichel M., Gutzwiller F., Berthoud S., Casabianca A., (1991) Psychoactive drug use among medical doctors is higher than in the general population. Social Science and Medicine (69). Similarly, the National Mental Health Survey of Doctors showed that younger doctors have the highest levels of moderate or high-risk alcohol use, using the AUDIT screening questionnaire (70) In another study using the AUDIT screen, 15% of a cohort of 3000 doctors practising in Australia were at risk of hazardous alcohol use (17% of men and 8% of women). (71) Personality factors and demographic factors, such as being male, middle aged (40-49 years) and being trained in Australia, were associated with alcohol abuse, whereas work related factors were not. The prevalence in doctors of other well-defined mental disorders, such as bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia, which are far less common in the community, is unknown.18.6.2 Personality disorders

As previously noted, the law defines ‘Impairment’ as a physical or mental impairment, disability, condition or disorder (including substance abuse or dependence) that detrimentally affects or is likely to, detrimentally affect the person’s capacity to practise the profession. This is often interpreted as meaning mental illness or substance disorder, while personality disorders, despite being recognized as mental disorders (72) are often not considered disorders despite their propensity to cause distress and dysfunction, particularly in the practice of medicine. Personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that involves significant and longstanding impairments in cognition (perception of self, others and events) affectivity (range, intensity and appropriateness of emotions) interpersonal functioning and impulse control. Personality traits (e.g. antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive) are enduring patterns of thinking about, relating to and perceiving self and others. We all have personality traits, and it is only when personality traits are maladaptive and cause dysfunction or distress to self or others that they constitute personality disorders (73) Although, the “physician personality” is often informally referred to as perfectionistic, hard-working, overly demanding of themselves and with an over exaggerated sense of responsibility towards patients (74), there are few formal studies of personality in doctors. Most descriptions are based on medical students and related to performance, which is not surprisingly predicted by conscientiousness and sociability (i.e. extraversion, openness, self‐esteem and neuroticism)(75) Personality also determines speciality career choice in medicine and there have been studies showing distinct personalities, for example of surgeons, and anaesthetists (76). Specifically, higher openness and lower conscientiousness has been associated with specializing in psychiatry, while lower openness and higher agreeableness has been associated with general practice, higher conscientiousness, lower agreeableness and neuroticism with surgery, and higher extraversion was associated with specializing in paediatrics. (Mullola, S., Hakulinen, C., Presseau, J. et al. Personality traits and career choices among physicians in Finland: employment sector, clinical patient contact, specialty and change of specialty. BMC Med Educ 18,52 (2018). Although referring to normative patterns of personality traits in doctors, these studies give us insight into some of the personality traits common in doctors that when held in extreme manifest in maladaptive patterns of behaviour and functioning that constitute personality disorder. For example, extraversion, agreeableness and openness are conducive to communication, but at their extreme expression in narcissism and borderline personality disorders they cause distress, manifesting in medicine as the “disruptive physician” (77) The following two cases illustrate the way in which personality disorder causes physician impairment. The first case is Health Care Complaints Commission v S [2015] NSWCATOD 99, involving a practitioner who was found to be impaired within the meaning of the Health Practitioner Regulation Law (NSW) by “virtue of a personality style and/or functioning which causes a pattern of behaviour towards patients that fails to observe appropriate professional boundaries”[at 135] . Otherwise he was not found to have either mental disorder or mental illness. What was notable in this case of ill-defined personality disorder, was that having declared that the practitioner suffered from an impairment and not competent to practise medicine, the Tribunal noted:-It is not necessary to define the condition suffered with a high level of precision, or in terms of narrow diagnostic labels (Grant v Health Care Complaints Commission [2003] NSWCA 73 at [11]).[ Health Care Complaints Commission v S [2015] NSWCATOD 99 [at 146]}}A 2015 case not only illustrated just how variable diagnostic opinion provided by expert witnesses can be on the issue personality disorder, but also the ways which personality disorders impact on practice. In that case the Occupational Division of the Civil and Administrative Tribunal of NSW (NCAT) cancelled the registration of a practitioner because it found that the practitioner had an impairment in the nature of a narcissistic personality disorder to such a degree that the practitioner did not have the capacity to practise medicine. (78) The first psychiatric expert considered whether the doctor in question, who was a general practitioner, had “an underlying health problem which leads [the practitioner] to hold the grandiose view of [the practitioner’s] practice skill, and leads [the practitioner] to practise in unreasonable isolation.” The expert concluded that:

on the basis of the relatively meagre clinical information currently available to me, I am once again unable to safely conclude that [the general practitioner] has any recognisable or diagnosable….. psychiatric disorder”.A second expert diagnosed narcissistic personality disorder, which would detrimentally affect the capacity to practise medicine in three ways:

Firstly [the general practitioner] is likely to make premature diagnostic decisions and not consider any differential diagnoses ... Secondly [the practitioner] has and will be likely in the future to ignore or neglect patients that disagree with {the practitioner] … Thirdly, [the practitioner’s] interpersonal manner will be significantly disruptive to the doctor-patient (and doctor-carer) relationship.A third expert agreed that the general practitioner had narcissistic personality traits but disagreed this represented a disorder because there was a lack of disruption in other parts of the practitioner’s personal life. That is, he was not thought to experience a disorder because any impact on his functions did not extend beyond his patients. NCAT found a number of the complaints proven and held that [the practitioner’s conduct] constituted professional misconduct. NCAT’s findings arose from the practitioner’s conduct involving a number of patients extending to misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment regime, poor communication skills, failure to display empathy and understanding of the needs of patients, propensity to diagnose certain conditions and failure to accept advice from peers. (79) In addition, NCAT accepted the evidence of the second expert, rejecting the evidence of the third expert, given serious concerns for patient safety expressed by the defendant’s supervisors:

[The practitioner’s] ability to practise medicine has been severely compromised, weakened and damaged because of the impact of [the practitioner’s] narcissistic personality disorder on [the practitioner’s] ability to diagnose appropriately, create appropriate treatment regimes, relate appropriately to patients, relate appropriately to [the practitioner’s]peers, and otherwise conduct himself in a manner appropriate to standards of behaviour expected within the community of medical practitioners. (80)NCAT found:

the evidence … led inexorably to the only possible conclusion, namely that [the practitioner], by reason of [the practitioner’s]impairment and the numerous failings in [the practitioner’s] medical knowledge, diagnosis, treatment and patient interrelationships, is incapable of practising safe medicine. The only conclusion open to us is that the respondent should not be permitted to continue to practise medicine in the interests of the protection of the public”. (81)Cases of impairment associated with personality disorder, which in theory may be lifelong, also raise the question of the time-frame within which an application may be made for the reinstatement of the practitioner’s registration. In this case, NCAT stated:

the evidence is that any improvement in the condition of the respondent will require intensive dynamic psychiatric treatment. On the evidence, the respondent has never undertaken such treatment because that which has been afforded to [the respondent] to date has been of a passive variety. There must be considerable doubt, therefore, whether the respondent will be able to overcome [the respondent’s] impairment, at the very least in the medium term. (82)In cancelling the practitioner’s registration, NCAT concluded that the practitioner was probably permanently unfit to practise safely and ordered that no application for review of its decision could be made for seven years. This arbitrary period of ineligibility for reinstatement of registration does highlight the difficulties in accessing, engaging in, and achieving remission even using evidence-based psychological treatments for people with a personality disorder.

18.7 The late career medical practitioner: cognitive impairment and other matters

The medical workforce is ageing in parallel with the general population. In 2015, 27.2 % of doctors were aged 55 or over (progressively increasing with each survey) with the average age being 45.6, oldest amongst specialists in general medicine (56.6) (as distinct from specific clinical specialities such as neurology, cardiology and gastroenterology amongst whom the average age was 50.1), followed by psychiatrists (53.1) and opthalmologists (53.0). (83) Whilst medical practitioners may anticipate a slightly longer life expectancy than the rest of the community, (84) they are not immune to age-related physical, cognitive and sensory changes that may interfere with practice. Specifically, with regards to cognitive ageing, there is great spread or heterogeneity across the population, even amongst highly educated individuals. Moreover, the ubiquitous age-related changes in cognition – specifically in relation to memory and processing speed – have wide inter-individual variation. Fluid intelligence, the capacity to think adaptively and apply critical or analytical reasoning tends to decline with age, while there is stabilisation or possibly improvement crystallised intelligence, a measure of accumulated knowledge and wisdom that is dependent on education and experience (85). This equally applies to doctors, amongst whom there are poor performers, but also “super-agers, ” namely a cohort of 15% of doctors over 75 who perform on neuropsychological testing in the average range of those aged less than 35 years (86) A computerized neuropsychological battery administered to 359 surgeons over 45 years at an American College Surgeons meeting showed age-related decline in attention, reaction time, visual learning, memory but scores were scores still superior to normative groups. However, this issue of normative comparisons is an important one, the important point being that we expect the cognitive performance of ageing doctors to be commensurate with that of younger doctors, not with general population. (87) Using the same methodology, Drag et al (2010) found that 61% of practising senior surgeons over 60 performed within range of the younger surgeons (45-59) on all cognitive tasks of visual sustained attention, reaction time, visual learning, memory; although this still varied with increasing age such that the performance of 78% of surgeons aged 60-64 years equaled younger peers, compared with 38% of those over 70 (88). Although on the surface this is reassuring that most ageing doctors are performing equally well on neuropsychological tests, “by and large” adequate cognitive functioning isn’t good enough for the profession. If one doctor is impaired then that is problematic. All we can say from these studies is that neuropsychological performance in doctors declines with age, and variably so. Clearly, there is no cut-off age where neuropsychological performance predictably deteriorates in doctors. The more pressing issue is, what is the ecological significance of these changes in terms of actual impact on the practice of medicine? Some 15 years ago, a landmark systematic review showed that physicians who have been in practice longer may be at risk for providing lower-quality care. Importantly, performance initially increases with increasing experience, peaks, and then decreases (89). Again this is a dimensional not a categorical finding. That is, performance appears to decline with age, not predictably with a defined cut-off age, and variably so. Waljee et al (2006) examined US Medicare files between 1998-1999 to explore the relationships between surgeon age and operative mortality in approximately 461, 000 patients undergoing eight specified procedures. They found that for some complex procedures (pancreatectomy, coronary artery bypass grafting and carotid endarterectomy), surgeons older than 60 years, particularly those with low procedure volumes, had higher operative mortality rates compared with younger counterparts, but for most procedures (oesophagectomy, cystectomy, lung resection, aortic valve replacement or aortic aneurysm repair), surgeon age was not an important predictor of operative risk, despite being of similar or even greater complexity (90) Similarly, in general, patients treated by older doctors have higher mortality rates than patient treated by younger doctors, except ageing doctors with high patient volume (91). We note that while low procedure volume and task complexity are often associated with poor performance in ageing doctors, working at lower volume is often a recommended workplace adaptation, it being difficult to strike the balance between case load and maintaining expertise (92). Another study of surgical outcomes of late-career opthlamologists performing 143,108 of 499 650 cataract operations is of relevance given that opthalmologists are amongst the oldest practising doctors in Australia. While late surgeon career stage was not associated with overall risk of surgical adverse events, it was associated with risk of dropped lens fragment (Odds Ratio, 2.30) and suspected endophthalmitis (Odds Ratio, 1.41). (93) While we can see a clear relationship between advancing age and doctors’ neuropsychological performance, and in turn between advancing age and a range of adverse clinical outcomes, this is a very complex relationship influenced by a range of heterogenous factors. The aforementioned studies have been based on normative studies of groups of doctors. An alternative way of looking at the relationship between poor performance and neuropsychological deficits can be gleaned from studies of doctors already identified and referred to regulatory agencies. For example, a study of 148 doctors (mean age 54 years; range 32-83) referred to the California Medical Board for complaints about misdiagnosis, surgical complications, inappropriate treatment or prescription found that they performed comparable to community-based norms, but demonstrated relative deficits on tests of sequential processing, attention, logical analysis, hand-eye coordination and verbal and non-verbal learning (94) Similarly, of 109 doctors and dentists referred to the UK's National Clinical Assessment Service for clinical difficulties, governance or safety issues, 20% scored below the standard cut-off score on a cognitive screening instrument, the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R). Some 13% were diagnosed with cognitive impairment after neuropsychological assessment, the youngest being 46 years. Many were working in isolation. Performance assessment results showed persistent failings in the practitioners' record keeping and clinical assessment. (95) As to the nature of impairment in older doctors who come to the attention of regulatory authorities, a study of the case records of 41 consecutive notifications of doctors aged 60 years and older to the Impaired Registrants Program of the then Medical Board of NSW showed that older doctors are at risk of the “four Ds”: depression, drink, drugs and dementia. The study reported dementia in 12%; cognitive impairment in 54%, substance abuse in 29% and depression in 22% (two comorbid psychiatric conditions were present in 17%). Consistent with the above study, typical neuropsychological findings included (i) preservation of long-term memory and consolidated verbal skills; (ii) auditory memory and learning abilities significantly lower than expected given superior verbal intelligence; (iii) decreased ability to commit novel information to memory and retain it after short delay; (iv) slowing of information processing, visual scanning, motor and mental slowing; (v) problems in planning, abstraction, cognitive flexibility and generativity; (vi) preserved ability to cope with routine medical problems and well-known patients by drawing on existing knowledge base; (vii) difficulty in dealing with complex or unusual problems; (viii) difficulty in retaining facts from recent patient consultations, recent reading; and (ix) tendency to be rigid and concrete in thinking. Two work patterns – the “workhorse” (high volume) and the “dabbler” (low volume) were observed, as was a culture of postponed retirement due to a sense of obligation and working “until you drop.” Impaired older doctors were found to have higher chronic illness burden compared with community norms, working in isolation or solo practice and almost half were the subject of patient complaints or of poor performance within ten years of presentation. There was an over-representation of GPs and overseas-trained doctors amongst those referred (96) After some 25 years of emerging science in the field of impaired ageing doctors, the profession is now tackling two complex questions: (i) how do we assess doctors referred to regulatory agencies and make sense of cognitive testing results which may or may not have true meaning for practice? and (ii) how do we detect and filter out doctors before they put the public, their colleagues and profession at risk, while retaining those still making a valuable contribution? We deal with the latter in the next section. With regards to the first, assessments of the ageing doctor must include a comprehensive assessment of global mental state and cognition.The gold standard assessment of cognition is neuropsychological assessment, sometimes called psychometric testing, which can identify relevant areas of concern, albeit the interpretation of such in terms of the real world and actual practise is often complex. Notwithstanding this caveat, there are some deficits that probably preclude competent practice. For instance, executive function is important for organisation and judgement, for instance weighing the pros and cons of potentially opposing diagnoses and treatment options. Specifically, working memory, the ability to hold different pieces of information simultaneously in one’s head, is important given a practitioner will need to integrate a patient’s current presentation, past history, test results, and so on before formulating a diagnosis and management plan. (97) Difficulties arise in determining the threshold for safe practice in the presence of broadly defined disorders such as cognitive impairment; a common reason for the referral of older practitioners to regulatory bodies. Cognitive impairment is a broad-dimensional construct that covers conditions ranging from Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) (98) to dementia, with resultant variation in its severity, rate of ongoing decline, and potential impact on practice. In some cases of MCI, such as those associated with substance abuse or depressive disorder, the degree of cognitive impairment may reverse to at least some extent with improvement in the underlying condition. Another factor to consider in interpreting whether an impairment would detrimentally affect the capacity to practise is the type and context of clinical practice. Every specialty relies differently on certain cognitive, physical and sensory skills, the notion of task-specific capacity being relevant here. For example, a tremor will have very different impact on the capacity to practise for a surgeon, as compared to a psychiatrist, as would visual acuity for a radiologist (99)18.8 Ageing and retirement

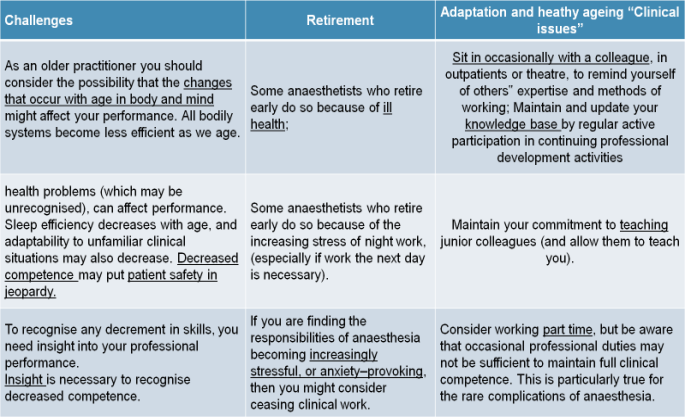

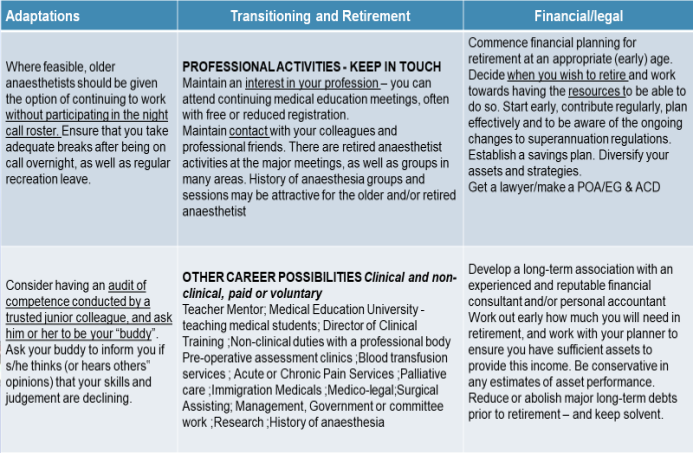

As stated above, the medical profession is ageing. Notwithstanding the huge interindividual variation in ageing, there are inevitable biopsychosocial changes with ageing, which potentially impact on competence (100)To this end, several of the Australian Colleges have long- recognized the importance of acknowledging the effects of ageing on medical practice and the need for preparing for retirement. For example, in 1996, the Australian College of Anaesthetists, Welfare of Anaesthetists Special Interest Group first promulgated the document: “Retirement and late career options for the older professional” with active pursuit of the objectives outlined in this document continuing to this day ( see Review Resource Document RD 04 (2016) www.anzca.edu.au/documents/fa-wel-sig-rd-04-retirement-20161011)). Tables 1 and 2 are directly derived from this document and provide practical examples of how all doctors, not just anaesthetists, can recognize and adapt to the challenges of ageing within the profession (101). Table 1 Table 2

Table 2

The Colleges of Surgery and Intensive Care Medicine have similar position statements and actively promote understanding of the challenges of ageing amongst their Fellows.(102)(103).

Notwithstanding these insights emanating from some areas of the profession, particularly the procedural specialists, the notion of planning for retirement is not routinely embedded within professional standards in practice. Unlike overseas and with other professions such as judges and pilots, there is no mandatory retirement age for doctors in Australia, so the community must rely upon the individual practitioner to plan actively and transition to retirement. The needs of each specialty are different in this regard (104)(105) (106) (107) (108).

It is not easy to know when “it is time” as acknowledged in by a NCAT decision involving a case of a 77 year old medical practitioner who was diagnosed with a cognitive disorder after a complaint to a regulatory authority. NCAT noted:

The Colleges of Surgery and Intensive Care Medicine have similar position statements and actively promote understanding of the challenges of ageing amongst their Fellows.(102)(103).

Notwithstanding these insights emanating from some areas of the profession, particularly the procedural specialists, the notion of planning for retirement is not routinely embedded within professional standards in practice. Unlike overseas and with other professions such as judges and pilots, there is no mandatory retirement age for doctors in Australia, so the community must rely upon the individual practitioner to plan actively and transition to retirement. The needs of each specialty are different in this regard (104)(105) (106) (107) (108).

It is not easy to know when “it is time” as acknowledged in by a NCAT decision involving a case of a 77 year old medical practitioner who was diagnosed with a cognitive disorder after a complaint to a regulatory authority. NCAT noted:

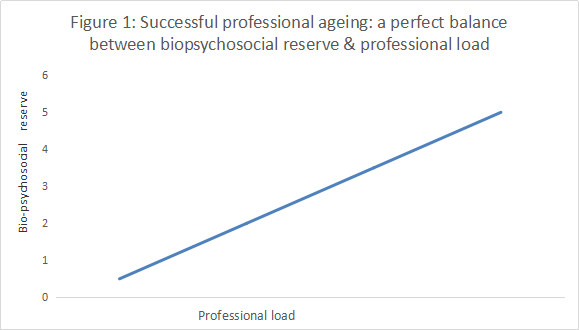

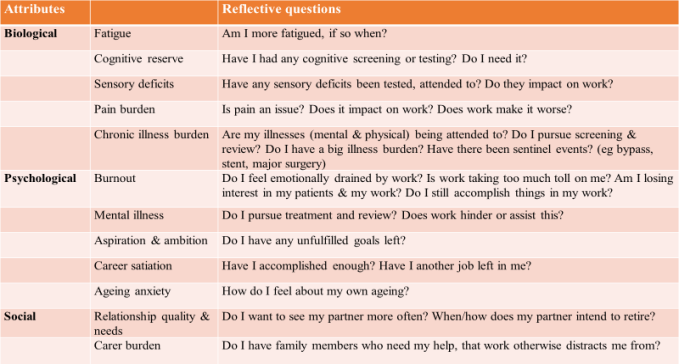

We recognise that it is sometimes difficult for a health practitioner, particularly a doctor, who may be self-employed or an independent contractor, to objectively assess that the time has arrived when the health and safety of the practitioner’s patients dictates that he or she should retire from practice. But practitioners have a duty to put the health and safety of the public before their own needs and desires. (109)This difficulty is not unusual. A cross-sectional survey of 1048 doctors aged 55 and over from a range of specialities showed that only 62% of doctors intended to retire (11.4% had no intention to retire and 26.6% were unsure). A broad array of psychosocial factors influenced this intention including financial resources, work centrality (ie how important work is to the doctors) emotional resources and the doctors’ own anxiety about ageing. Wijeratne C, Earl JK, Peisah C, Luscombe GM, Tibbertsma J. (2017) Professional and psychosocial factors affecting the intention to retire of Australian medical practitioners. Med J Aust.206(5):209-214. To promote the concept that self-care and preparing for ageing and retirement is part of responsible professional practice, we have developed the notion of successful ageing. Notably doctors aged 60 or older from Australia, Canada and the United States deemed to be “ageing well” by peers demonstrated: (i) insights into the physical and psychological vicissitudes of ageing and the effects of such on practice; (ii) the need for adaptations in working hours and choice of work; (iii) the importance of long-term retirement planning; (iv) the usefulness of a transitional phase to ease into retirement; and (v) the need to cultivate a variety of medical and non-medical pursuits and relationships early in one's career. (110). Notably, although related, personal successful ageing in doctors is distinct from occupational successful ageing, although occupational factors such as greater work centrality, fewer work adaptations and less retirement planning is associated with perceived personal successful ageing in doctors. This suggests that the older doctor’s sense of "success" is intertwined with continuing practice (111) Another interesting observation is that female doctors, particularly single female doctors “do this (ageing) better”. Women intend to retire earlier. Younger cohort and married women more frequently viewed their career as a calling, while women in general, and single women more frequently, endorsed personal successful aging more than men (112). Self-reflection and individual retirement planning with insight has been encouraged and is part of professional practise. As such, the key to successful ageing in doctors is having insight into one’s reserve and capabilities in the context of stressors, burdens and vulnerabilities. Perhaps when load and burden exceed capabilities then it is time to consider retirement. See Figure 1 and Table 3. Figure 1 (adapted from Peisah C. Successful ageing for psychiatrists Australasian Psychiatry 2016; 24:126-130)