4. The JP Traffic Court Process

A. Explanation of the courtroom

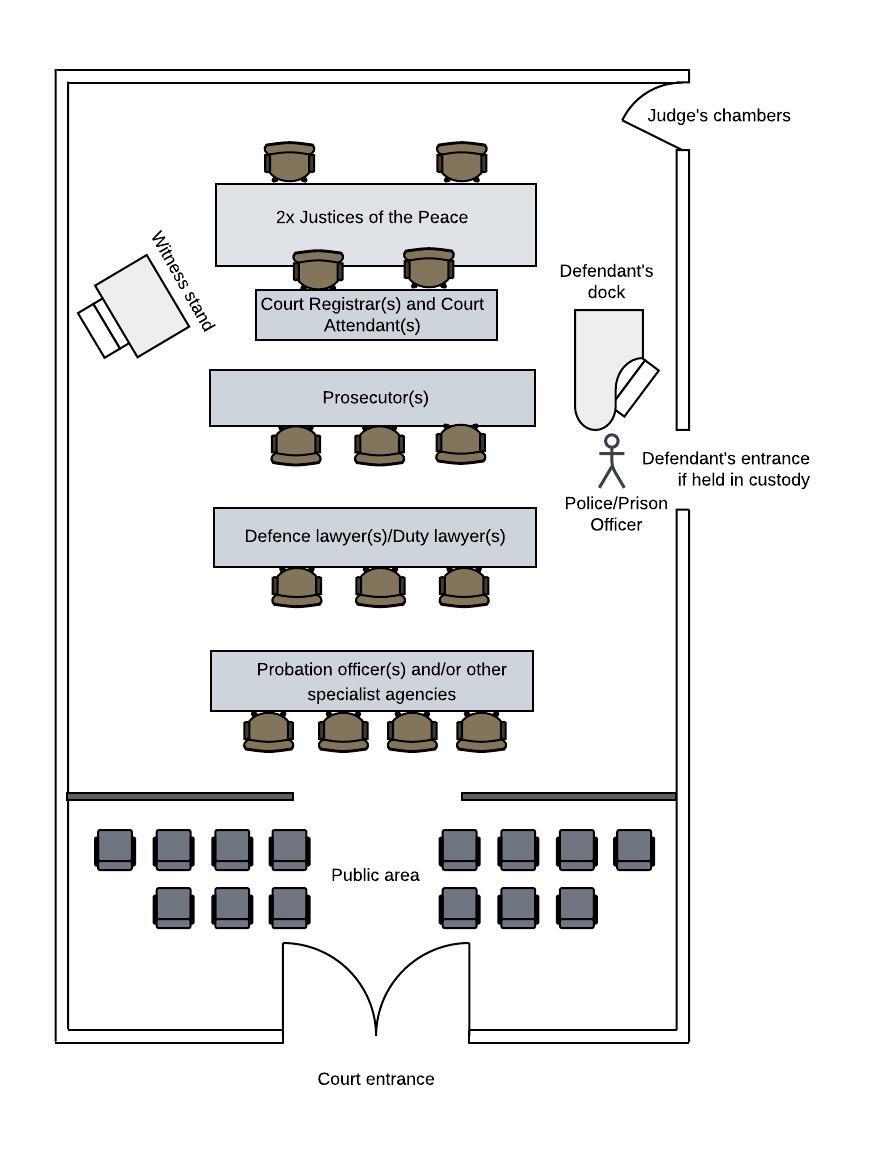

Two Justices of the Peace hear traffic offences in the District Court on a Judge-alone trial. This means that there is no jury present.

The District Courtroom usually looks like this:

Key figures in the JP Traffic Court process:

1. Justice of the Peace

Key figures in the JP Traffic Court process:

1. Justice of the Peace

Justices of the Peace in New Zealand are appointed by the Governor-General in recognition that they are community members of good stature. On a volunteer basis, they are authorised to do a number of official roles in the community. Some Justices of the Peace are Judicial Justices who undertake judicial duties relating to minor offences instead of a Judge in the District Court.

Regarding traffic offences, two or more Justices of the Peace have the authority to preside over the District Court relating to category 1 offending under certain parts of the Land Transport Act 1998 and under regulations created by that Act: section 135(2) LTA.

The JPs will hear the prosecution’s case against you, hear your case (presented by yourself or your lawyer) and tell you any next steps in your case or the outcome of your case and (if any) explain your penalty.

2. Court Registrar

Court Registrars manage a court case by processing applications, ensuring the Justices of the Peace have everything they need to hear your case. They sit in front of the JPs in the courtroom and are often on their computers updating the case as it progresses.

3. Court Attendant

Court Attendants assist the Court and members of the public to ensure court processes run smoothly.

4. Prosecutor

The Police Prosecutor’s role is to present the case against you to the JPs. They will elaborate on anything about the alleged offending that the JPs do not have in the summary of facts and present new information if necessary.

5. Defence Lawyers

You have the option to be represented by a lawyer in court: section 11 CPA; section 24 New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990.

You can choose to engage a lawyer yourself or be represented by a Duty Lawyer on the day.

A Duty Lawyer is a lawyer available at court to help you if you have been charged with an offence and do not have a lawyer to represent you. Duty Lawyers can advise and represent you on the day, help you decide whether to plead guilty or not guilty and sometimes help you apply for legal aid if your case is ongoing.

Duty Lawyers are usually only available for first appearances on each charge. If you wish to have a Duty Lawyer represent you, you should arrive at court early on the day of your hearing and ask the court staff to direct you to a Duty Lawyer.

The role of a Defence Lawyer (whether a Duty Lawyer or a lawyer you have paid to represent you) is to defend the case against you. Even if you plead guilty to a charge, the defence lawyer may be able to argue that the JPs should reduce your penalty due to mitigating factors.

6. Probation Officers and other specialist agencies

If it is relevant to the case at hand, the JPs may ask probation officers or other specialist agencies (for example, restorative justice, alcohol and drug support coordinators) for reports about your offending history (if any) and other relevant factors to help determine which sentencing option is appropriate.

7. Witnesses

Witnesses are summoned to the Court when their evidence is deemed essential to the case. Witnesses provide information about what happened or about some other aspect of the case. A witness can be called for either the prosecution or the defence.

B. What are each of the appearances?

First appearance

Your summons document or notice of hearing will tell you when you need to appear in court. This will be your first appearance. The Registrar will call your name and you have to enter the courtroom and stand beside the dock (only those offences that can result in prison sentences stand in the dock).

The charge against you will be read out, and then you or the lawyer representing you will tell the Court whether you plead guilty or not guilty. You should be aware that you have the right to enter your plea (i.e.. tell the Court that you are guilty or not guilty) any time before your first appearance by filing a notice: section 38(1) CPA. If you do this, you do not have to appear in court to enter your plea.

If you are not ready to enter a plea before or at your first appearance, you can ask the case to be put off to a later date so that you can seek legal advice or consider other information. This is called a “remand without plea”. Depending on the Court, the remand will usually be for one to two weeks.

If you plead guilty, you will usually be sentenced at the first hearing and you will not have to appear in Court again regarding that charge. See Part 4(D) of this Guide for an explanation of entering a guilty plea.

If you plead not guilty, a date will be set to appear in Court again for a Judge-alone trial.

Defended hearing

A defended hearing (sometimes called a “judge-alone trial”) is where the JPs will hear both your case (or, if applicable, the case that your lawyer presents) and the case against you by the prosecution. Witnesses (if any) will also be questioned by either the prosecution, yourself (or the lawyer representing you), or both parties. The JPs will usually decide the verdict (i.e. whether the charge is proved or dismissed) on the same day. If the charge is proved, sentencing will usually take place at this hearing and you will not have to appear again regarding the charge. See Part 4(F) of this Guidefor a detailed explanation of what happens at a defended hearing.

A formal proof hearing occurs when you have failed to appear for your first appearance and you have not entered a plea before the appearance. The Court can proceed with the trial without you and will proceed as if you have entered a plea of not guilty: sections 119(2) and (3) CPA.

Formal proof is a mini trial on the evidence by the prosecution produced through an affidavit. The Court may call this dealing with the case “on the papers”. The Court has to be satisfied that the prosecution’s cause of action is established, meaning that, from the evidence of the affidavit, you have committed the offence that the prosecution alleges you committed. The Justices will be proactive in examining the affidavit to ensure information to prove the cause of action is established, but there will be no defence from your side. See Part 4(G) of this Guide for a detailed explanation about what happens at a formal proof hearing.

Sentencing

Sentencing is the process of the Justices determining the penalty for the offence. Sentencing occurs after the defendant pleads guilty or after a judge-alone trial where the charge is found proven. It will usually take place immediately unless the JPs request a pre-sentencing report from the Department of Corrections. See Part 4(H) of this Guide for a detailed explanation about what happens at sentencing.

C. What are the documents?

The Criminal Disclosure Act 2008 (“CDA”) requires prosecutors to inform you of certain information. This is split into two categories: initial disclosure and full disclosure. Disclosure can happen by post, electronic means or personal delivery.

Initial Disclosure

Initial disclosure is the information which you must be given when the police choose to begin proceedings (or as soon as is reasonable after that). You will be given three things in initial disclosure: charging document, summary of facts and your criminal history.

-

Charging document

A charging document is the formal method of accusing someone of breaking the law.

It includes a range of information including:

-

Information about the charge:

-

What you are charged with;

-

What categories of offence the charge is for; and

-

What the maximum penalty for the charge is;

-

-

Particulars of the prosecutor and defendant;

-

Information about the court:

-

Which court it will be heard in; and

-

When the first appearance in court is;

-

-

A statement saying the prosecution has good cause to suspect the defendant committed the charge.

-

Summary of facts

As well as the charging document, a defendant is provided with a summary of facts. Sometimes called a caption sheet, this is the prosecution’s understanding of the events. This provides a quick summary of what the prosecutor believes happened, and if you plead guilty, these are often the key facts that the Court will use to determine your sentence.

-

Criminal history

The third requirement of initial disclosure is a list of the defendant’s previous convictions. This is used for both proof and sentencing. Many traffic offences (such as driving while disqualified: section 32 LTA) distinguish between first and second or third offences. If this is a repeat offence, the law often requires higher sentences or a different offence altogether.

This is also a useful for ensuring that the defendant’s conviction history is correct. If you are a defendant and your conviction history is incorrect, you have the opportunity to correct any errors before sentencing.

Full Disclosure

Full disclosure is all of the information that the prosecution must give you. This occurs after a not-guilty plea is entered and must be given to you as soon as reasonably practicable. Full disclosure is broad and covers anything relevant (with some exceptions found in section 16 CDA). Typical documents covered in full disclosure in traffic courts include formal statements, crash reports, photographs and certificates.

-

Formal statements

A formal statement is a statement of any potential witness. It contains a brief of the evidence the witness will give and a declaration that this evidence is true.

-

Crash Report

A traffic crash report held by the police is a document that may be disclosed if it is relevant to the proceedings. This can contain information about the crash, drivers, vehicles, witnesses, road conditions, and probable cause.

-

Photographs

Failure to disclose a photograph has caused previous prosecutions to fail. In the case Tonihi v Police HC Rotorua CRI-2006-463-47, a photograph was not disclosed, which eventually resulted in the conviction being overturned on appeal because the photograph created doubt about the driver’s identity.

-

Certificates

For some offences, such as drink driving, the prosecution may use certificates to prove the proper taking of blood samples: sections 72 to 75 LTA. The certificate system allows the prosecution to show that the testing was reliable without requiring evidence from every step of the process. There are procedural requirements under the act for certification. This also provides a narrow range of exceptions where evidence may still be required under section 79 of the LTA.

D. Entering a Plea

Once initial disclosure has occurred, defendants are required to enter a plea: either guilty, not guilty or a special plea.

Guilty plea

A guilty plea means that you admit you did the offence you have been charged with. You can enter your guilty plea in person or by notice (by sending a letter or email) for JP Traffic Court offences.

The Court will then decide your sentence. When entering a guilty plea for a category 1 offence (which gets heard in traffic court), you can indicate whether or not you wish to be present for sentencing. If so, you will be able to have your say on what your sentence is. You can also include written submissions with your guilty plea, which the JPs can consider when determining your sentence. Otherwise, the JPs will determine your sentence according to their guidelines and the information available.

Not guilty plea

A not guilty plea is the legal way of saying that you did not do the offence. If you were not the driver of the vehicle, you can nominate the offender by a sworn affidavit: click this link for an example of a sworn affidavit nominating the offender. If you plead not guilty, the trial will proceed and the JPs will determine whether they think you are guilty.

Special pleasThree special pleas are applicable in exceptional circumstances. The pleas of previous acquittal and previous conviction maintain the rule against double jeopardy. Simply put, you cannot be tried twice for the same events. This applies if you have been previously convicted or acquitted for either the same offence or another offence arising from the same facts. You can also enter a plea of pardon if you have received a pardon.

E. What if you do not attend Court?

The Court will contact you to attend your first appearance (via a summons document/notice of hearing), where you may enter your plea (you also have the choice to lodge your plea by letter or email). You must attend court when you have been summoned to attend a hearing, as defendants are expected to be present at all hearings concerning a charge against them: section 117 CPA.

If you choose to enter a guilty plea at any point leading up to the hearing, you may indicate to the Court that you do not wish to be present for sentencing: section 38 CPA.

Alternatively, if you have a reasonable concern as to why you are unable to attend the hearing (for instance, illness), communicate this to the Court, and you may be granted an exemption from appearing: section 118(2)(a) CPA.

Non-attendance of defendant charged with category 1 offence:

If you fail to attend court without providing a reason nor a plea indication, the JPs may proceed with the hearing on the basis that you have entered a not-guilty plea, or they may set a date for a formal proof hearing: s 119(2) and (3) CPA.

What if you were not notified, and a sentence/order has been imposed on you?

If you have a reasonable excuse as to why you were unable to attend the hearing that was unknown to the Court at the time, you have the ability to apply for a rehearing of your case: section 126 CPA. For category 1 offences, the Registrar has the power to make an application for a rehearing if (1) you were not correctly notified of the first hearing and (2) the prosecutor does not object: section 127 CPA.

The application must be:

-

Filed in the same court that you received the sentence or order from; and

-

Filed within 15 working days after receiving the notice.

Will you get a warrant?

You will not receive a warrant from the JP Court, as warrants can generally not be issued by JPs for category 1 offences. One exception is if, at the hearing, in your absence, the JPs have reason to believe that a community-based sentence is appropriate. In this case, you may be issued a summons (an order) to appear before the Court or be issued a warrant to arrest to bring you before the Court: section 119(4)-(5) CPA.

Will the Court deal with the charges in your absence?

The JPs will determine your guilt based on what information they have available to them. The prosecutor will make submissions on what they think is an appropriate outcome for your case. It is important to note that without your presence, the Court will consider the charges without knowledge of your personal circumstances.

F. What happens at a defended hearing (judge-alone trial)?

If you have pleaded not guilty and wish to challenge your charge, you may represent yourself in a defended hearing (judge-alone trial): section 11(b) CPA. A defended hearing (sometimes referred to as a substantive hearing) is an opportunity to provide your own evidence and submissions in front of the JPs. The prosecutor will also provide their evidence and version of events to the Court.

Notes:

-

Upon arriving at the District Court, wait outside the courtroom and the Registrar will call you in when your case is up.

-

During the hearing process, the JPs will let you know when it is your turn to speak, at this time you are free to ask the JPs questions on any points of confusion. It is recommended you do both your own research and then follow the guidance from the JP’s.

-

If you are self-representing, you maintain two distinct role: as an advocate and as a witness. You will advocate and provide submissions about the law accompanied with arguments for your case. When you are a witness giving evidence, you may only talk about events. You may not provide evidence when speaking as an advocate from the bench.

The Police Case

-

Opening statement

The Criminal Procedure Act (section 105) assumes that judges/justices at judge-alone trials can understand and digest evidence without opening and closing statements from counsel. However, the prosecutor will likely provide a brief introduction and opening statement. This may only include the prosecution’s case and a short outline of the charge the defendant is facing: section 105(1)(a) CPA.

-

Witnesses giving evidence

Witnesses will usually read out their brief of evidence, a statement read in court by a witness from the witness stand. This should include what happened, the order of events, how other people conducted themselves and what they did.

-

Cross examination

What is it?

The cross-examination aims to point out any weaknesses in the opposition's evidence, and to test a witness's version of events. Any witness you bring to Court can also be cross-examined by opposing counsel.

What kind of questions to ask?

In a cross-examination, there are no restrictions on asking leading questions: section 84 Evidence Act 2006. A leading question is one that prompts or encourages someone to give a predetermined answer. You are allowed to frame questions in a way that will elicit a helpful response for your case. However, a JP may interrupt you if they believe your questioning is irrelevant, damaging, humiliating or belittling to the witness.

Ask questions that are both relevant and have a justifiable foundation for being asked. Section 85 of the Evidence Act further outlines what the Court will deem ‘unacceptable questioning.’

General advice:

-

Keep your questions short and succinct;

-

Use plain and simple language;

-

Confidently take control of your cross examination;

-

Ask leading questions that suggest an answer; and

-

Try and do most the talking, avoid having the witness re-state their version of events.

-

Re-examination

This is an opportunity for counsel to question their witness again. If any new information has arisen in the cross-examination, clarify those matters here. No new information can be introduced when re-examining a witness. You can only use a re-examination to clarify what occurred in cross-examination: section 97 Evidence Act. You may not ask leading questions in a re-examination.

Your Case

-

What to bring

Bring any evidence that helps explain your version of events, such as photos, maps, statements or notices. When preparing your case, research the section of the legislation that contains the offence you are being charged with and the elements of the offence. In preparation, Community Law is a useful resource to ensure you are looking at the correct rules and legislation.

Ensure that all documentation and testimony that you provide the court is truthful to the best of your knowledge, take all reasonable steps to ensure the evidence is correct and that you have done everything to avoid misleading the court. Failure to do so can be considered a criminal offence.

Note: When preparing your case for a defended hearing in the JP Traffic Court, focus your preparation on the Evidence Act 2006 and the Criminal Procedure Act 2011.

Opening statementIn your opening statement, introduce yourself to the Court and identify the issues at hand in a clearly and concisely. You may include a general statement about your understanding of the case and identify the issues: section 105(1)(b) CPA.

Note: When addressing the JPs, refer to them as “Your Worship” not “Your Honour.”

-

Giving evidence

What kind of things you should talk about:

When giving evidence as a witness, you must only speak to what you saw, heard and did. You must not testify about what someone else may have seen or heard. It is also important not to propose arguments when giving evidence, as you may only advocate for yourself from the counsel table.

Giving evidence will take the form of a conversation between you and the JPs. Discuss your version of the events that took place, outlining the relevant details you recall.

In general:

-

Speak clear and simply;

-

Focus on key points (elements of your charge);

-

Treat your advocacy like a conversation with the JP, and answer any questions they ask you truthfully;

-

Do not mislead at any point; and

-

Tell the truth to maintain your credibility.

How to produce an exhibit:

An exhibit is an article or object of any kind that can be produced as evidence on behalf of either the prosecutor or the defendant. Exhibits are often referred to within a sworn affidavit. This is where you write out your evidence in written form, in front of a person authorised to take declarations and administer oaths. Authorised persons include a Court Registrar or Deputy Registrar of the District or High Court, a JP or an enrolled barrister or solicitor.

An affidavit can be used by any party, and may only be read/used once it has been correctly filed.

Your affidavit must:

-

Be written in first person;

-

State the name, occupation, and place of residency of the person making it;

-

Include all the written evidence that you wish to present;

-

Only include necessary material;

-

Be signed by you in the presence of the person taking your oath; and

-

To the best of your knowledge and belief, be truthful.

Filing formalities:

-

If the affidavit is more than one page long, ensure the deponent (the statement-maker) has initialled or marked each page.

-

If you have made a mistake in your affidavit, immediately notify the Court and they may instruct you to create a supplementary affidavit.

Exhibits:

-

Where your affidavit has referenced extra evidence/additional documents (i.e letters, bank statements), these too must be attached and clearly marked as an exhibit.

-

If you make any alterations, they must also be initialled.

-

-

An exhibit to an affidavit must be marked with a distinguishing letter or number (or both) and if practicable, annexed to the affidavit at the time of filing and service.

-

For instance an affidavit may be marked, “Letter from Police, dated 11/11/11, EXHIBIT A”

-

The exhibit itself must then also be marked (for example, the letter itself should display the letter ‘A’).

-

If you have chosen to testify (given evidence), the prosecutor has a right to cross-examine you. When being cross-examined, take your time when answering questions, as the cross examiner will be trying to shape a desired response.

When you are being cross examined, there is a duty on the prosecutor ‘to put to the case’: section 92 Evidence Act. This means allowing you to respond to any disputed aspects of your testimony.

Therefore, you can expect to be cross examined on:

-

Significant matters in the proceedings:

-

Matters must be relevant and in issue;

-

Any matters that contradict your evidence; and

-

Anything you may reasonably be expected to be in a position to give admissible evidence on.

General advice:

-

Take your time when answering questions

-

Ask for a question to be clarified if you do not understand it

-

Tell the truth.

What you can talk about after being cross examined:

After being cross-examined, you may be subject to a re-examination to clarify any points of ambiguity. The same rule applies here as for re-examination (above).

-

Calling witnesses

If you would like someone else to testify on your behalf (i.e. if they were present at the alleged offending or able to provide useful and relevant information), you may call a witness. Ensure that they are prepared with what they will say on the stand. Any witness you call will have the right to be cross-examined by the prosecutor.

Closing statements

The prosecutor may provide a closing address once all evidence has been given, including any rebuttal or re-examination. Following this, you also may make closing statements, and the prosecutor will have no right to reply: section 107(6) and (7) CPA. A closing statement will summarise your theory of the case, reiterate any useful evidence that arose during the trial and restate your arguments. You may wish to point out any weaknesses in the opposition evidence that you may have noticed.

It is important not to mention any new evidence or arguments.

The decision

At defended hearings, the JPs will make the decision at the end of the hearing or shortly after. The JPs must give reasons for their decision, but may provide these reasons at a later date: section 106(2) and (7) CPA.

G. What happens at a formal proof hearing?

What happens at a formal proof hearing?

A formal proof hearing is where you have failed to attend court when requested. In your absence, the JPs must deliberate on your offending and will do so with police evidence, formal statements and by affidavit.

The police case

What is given to the Court?

Any evidence that supports the charge is given to the Court at formal proof.This will include the prosecution’s summary of facts, any relevant criminal history and the charging document.

The police case may also include:

-

Statements from the officers involved;

-

Service of notices (i.e. suspension notices);

-

Certificates of the equipment used (breath testing equipment, speed/radar devices);

-

Photographs (i.e. images taken of insecure loads).

Do the witnesses still come and give verbal evidence?

Witnesses can still attend court should they wish to appear. However, witness evidence does not have to be verbal; a written statement read by the JPs will suffice.

What information is put forward about you?

Information that the Police have about the charge, facts and circumstances of the offending may all be offered to the Court.

The decision

The JPs will assess the evidence before them, often considering evidence from sworn police testimonies. They can provide a conviction if the charge is proven beyond reasonable doubt.

H. Sentencing

What is sentencing and when does it happen?

Sentencing is the process of a Judge (or, in this case, a JP) imposing a punishment on the defendant once the defendant has pleaded guilty or a charge is found proven at a defended hearing.

The process for sentencing is slightly different after a guilty plea during a first appearance and after a charge has been found proven during a defended hearing. Nevertheless, the general process is as follows:

Sentencing in the District Court usually takes place immediately. After the JPs have read the summary of facts or have had it read to them by the Prosecutor, the JPs will also read a confirmed list of previous convictions (if any). At this point, the JPs may request a stand-down report or a pre-sentence report relating to your offending history (if any). It may be more common for these reports to be requested following a charge being found proven in a defended hearing.

-

A stand-down report is when the JPs ask for a Community Corrections report on the appropriate sentence. The defendant “stands down” from court for a while and discusses various options with Community Corrections (a probation officer) who will usually prepare a report. The report (or oral recommendations) will be read back to the court when the case is called again.

-

A full pre-sentence report is usually only required in more serious cases or where some issues that should be brought to the attention of the Court before sentencing. The case is adjourned until the report is prepared. This report is more detailed than a stand-down report because it includes an assessment of the defendant’s risk of reoffending. JPs give these reports considerable weight when determining appropriate sentences.

After the JPs have read a confirmed list of your previous convictions or have requested a stand-down/pre-sentence report, you can make submissions to the JPs about what sort of sentence you are advocating for. This is called a plea in mitigation, usually aimed at reducing the sentence. After your submissions, the prosecutor may make submissions if requested by the JPs.

Taking into account all information, the JPs will tell you and the rest of the Court your sentence.

What kind of sentencing outcomes are available to the court?There are several different sentencing outcomes available to the court. In deciding which option is most appropriate, the JP will take into account a number of factors, including the seriousness of the offending and your degree of blame, the seriousness of the type of offence, your family, whānau, community, cultural and socio-economic background.

Different options the Court can take:

-

-

Infringement offences

-

Fineable only offences: you will not receive a conviction and therefore will not have a criminal record: section 375 CPA.

Category 1 offencesConviction: a formal declaration by the Court that you are guilty of a criminal offence. A sentence (penalty) is usually imposed as a punishment.

Discharge without conviction: you will not receive a conviction because the Court has deemed that the direct and indirect consequences of a conviction would be out of all proportion to the gravity of the offence: section 107 Sentencing Act 2002 (“SA”). Deemed to be an acquittal (where the Court deems that you are not guilty of the crime with which you have been charged). Not available where the Court is required by legislation to impose a minimum sentence: section 106 SA.

Conviction and discharge: you will receive a conviction (and therefore, the charge will be on your criminal record), but you will not receive a sentence. Used where the Court accepts that you are guilty of the offence but believes that because the offending was minor, a conviction alone is a sufficient punishment. Not available where the Court is required by legislation to impose a minimum sentence: section 108 SA.

Order to come up for sentence if called on: this order results in a conviction (the charge will appear on your permanent record) but you will not be sentenced provided you do not commit any further offences within a period of one year from the date of conviction: section 110 SA. It is less common for this option to be imposed in the JP Traffic Court.

Types of sentences/orders:The type of penalty (punishment) you can expect during sentencing is usually prescribed by the offence provision in the relevant legislation. Those penalties which JPs can impose are as follows:

Fines:

A fine is the most common sentence a JP will order against a defendant. The maximum amount that a JP can fine is usually prescribed within the offence provision of the relevant legislation. While it is common sentencing practice for the courts to regard a fine as the appropriate sentence (section 13 SA) there are many factors that may make a court deem another sentence as more appropriate, for example, the financial capacity of the offender to pay the fine (section 14 SA).

Where the minimum amount for the fine is not prescribed by the relevant offence provision and only a maximum amount is prescribed, the JPs have the discretion to set the amount of the fine up until that maximum amount. In setting the fine, they will take into account a number of factors, including the financial capacity of the offender and sentencing principles contained in sections 7-10 of the Sentencing Act.

Reparation:

A JP can order you to pay reparation to a victim involved in your offending (if any). Reparation is paid to the victim as compensation for loss/damage to property or emotional harm: section 32(1) SA.

A sentence of reparation may be imposed on its own or as well as a fine: section 12 SA.

License disqualification:

Justices of the Peace have discretion to order a licence disqualification alongside another sentence or on its own if the Court is satisfied that the offence relates to road safety: section 80 LTA. In most cases, JPs have discretion to set the disqualification for a period they see fit, considering the need to protect the public. However, some provisions in the LTA provide mandatory minimum periods for disqualification.

Confiscation of motor vehicle:

In limited circumstances, JPs can order a defendant’s motor vehicle to be confiscated: section 128 SA. For example, JPs have discretion to confiscate a motor vehicle where the defendant has been convicted of an offence in section 59 of the Land Transport Act (relating to failure or refusal to remain at a specified place or to accompany an enforcement officer). This order can be made in addition to, or instead of, imposing another sentence or making any other order: section 128(4) SA.

The offender does not have to own or be in charge of the motor vehicle at the time of offending for the Court to confiscate it: section 128(2) SA.

In exercising discretion to confiscate a vehicle, the JPs will have regard to several factors including any hardship confiscation would cause the offender or another person who would otherwise have had the benefit of the motor vehicle’s use on a regular basis, and the nature and extent of the offender or any other person’s interest in the motor vehicle: section 128(5) SA.

While JPs have jurisdiction to make these orders, in reality, they may refer the decision to confiscate a motor vehicle to a Judge.

Court costs:

Along with the penalty imposed by the Court, it is not uncommon for the JPs to order a defendant to pay the Court $130 for court costs.

Prosecution’s costs:

There is also potential that a defendant will be ordered to pay the costs of the prosecution. This is likely to occur where a discharge without conviction has been granted or where there has been unnecessary prolonging of a trial or hearing by the defence.

Talking to the Justices of the Peace about your personal circumstances/plea in mitigation:

If you plead guilty, you or your lawyer can present to the court a “plea in mitigation.” This is the process of telling the JPs about any special circumstances that should be considered before giving you your sentence. This could reduce your sentence by highlighting the factors that lessen (“mitigate”) the seriousness of your offence.

Your plea in mitigation could include character references (explaining that the offending was out of character for you) an explanation of any relevant personal circumstances at the time you committed the offence (income, dependents, employment history, medical history, living arrangements) and your response to offending, for example, if you have shown remorse, if you have accepted responsibility, if you have apologised to the victim (if any) and if you’ve been to counselling.

Sentencing at a formal proof hearing:

For all non-imprisonable offences (offences which JPs can hear) defendants can be sentenced in their absence.

Re-hearing in certain circumstances:

If the defendant was not notified of the sentencing hearing, the Court must order a retrial: section 126(7) CPA. The Court may also order a rehearing in a situation where the Court is satisfied that the defendant was notified of the hearing and had a reasonable excuse for non-attendance at the hearing, but that was not known to the Court at the time, and it is in the interests of justice to do so: section 126(6) CPA.

Application for re-sentencing:

A defendant who is sentenced in their absence for a category 1 offence may apply for a rehearing concerning the sentence imposed by the court: section 126 CPA. This situation does not apply where a defendant pleads guilty by notice and did not indicate that they wished to attend the sentencing hearing: section 118(2)(d) CPA. In this situation, the defendant may make an application under section 177 CPA. However, please note that a defendant cannot apply for a rehearing under section 126 and section 177: section 177(6) CPA.

Will you get a conviction?

If you plead guilty or are found guilty of an infringement offence, you will not receive a criminal conviction: section 375 CPA.

If you plead guilty or are found guilty of a category 1 offence you will receive a criminal conviction unless you are discharged without conviction.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding AustLII Communities? Send feedback